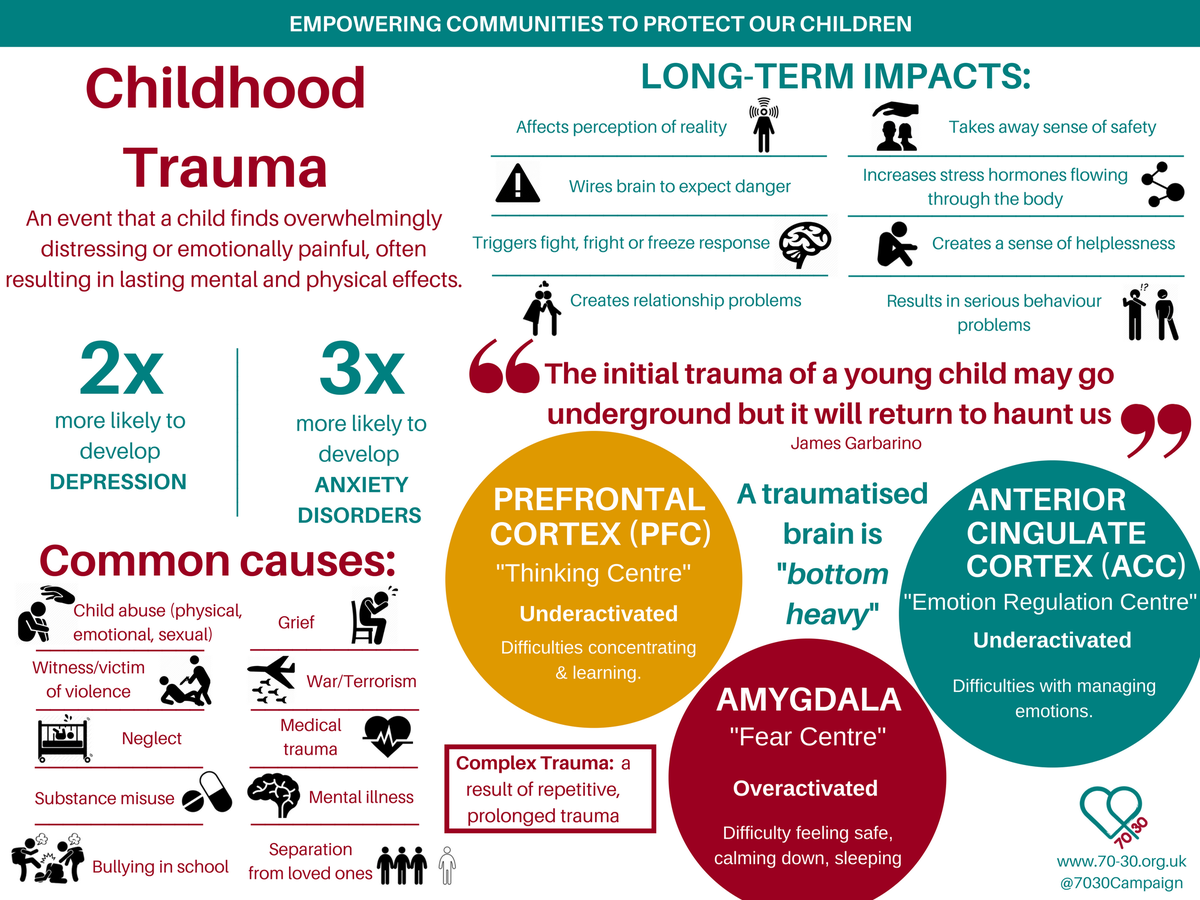

There is a lot of buzz in the world of education about "Trauma Informed Practices" and Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE's) research alerting educators to the impacts of traumatic experiences on early developing brains and calling for more training and understanding of these practices. The infographic below is an example of the kind of information that is imparted to educators in trainings on childhood trauma.

|

| Source: https://www.focusforhealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/childhood-traumas-graphic.png |

Don't get me wrong, as you read this post, I believe the statistics and the research on trauma's impacts. But, I do think there can be a tendency for educators to over-generalize the negative effects of traumatic experiences to all children who are at risk for having these outcomes.

I have been consulting, coaching and training teachers in Head Start and Preschool Expansion Grant (children from families at or below 200% poverty level) classrooms for the last three years on how to increase their practices with The Pyramid Model social and emotional teaching framework. I use the Teaching Pyramid Observational Tool to measure the percentage of these practices teachers are using in their classrooms.

Overall, teachers in these classrooms are working with preschool aged children (and some infants and toddlers) where they are concerned with the challenging behavior that these kids are using. In coaching conversations, when we are creating action plans and I am asking reflective questions, I have heard teachers say things like, "Well, for the population that I teach, I just don't think it will work." Or, "These kids need so much and their lives are so difficult. It's not like teaching a typical preschool group." And, I swear this one is a direct quote, "I mourn for these kids and the terrible home-lives they have." These, and other similar comments are not uncommon for me to hear.

What bothers me about comments like that, is that the teachers who say them are coming from a deficit mindset about the kids they are teaching. There is a note a pity to them that I find somewhat infuriating and always frustrating. They make assumptions of kids abilities (or lack thereof) based on background information. Challenging behavior (i.e. swearing, hitting, taking toys) is looked at as the failing of parents to be good role models for positive discipline. Or, it is the result of the opioid crisis and parents with substance use disorder, which is a problem that may feel is too overwhelming.

While this is a long quote, it has been one of my favorites since I read the book Happiness by Aminata Forna. It illustrates the problem with this deficit lens of trauma. The character, Atilla, is a psychologist who helps support communities who have been through traumatic events such as war or oppression. This is his response to a graduate student who has just said that she is curious about what damage will be manifested in the people in her trauma study.

“There is nothing in

evitable about the impact of trauma, except perhaps the way the victim is going

to be treated by professionals like us, who then ascribe every subsequent

difficulty in their lives to what has happened to them in the past. We don’t

blame victims any longer, instead we condemn them. We treat them like damaged

goods and in so doing we compound the pain of whatever wound has been inflicted

and we encourage everyone around them to do the same. The fact of the matter is

that most people who have endured trauma do so without lasting negative

effects, but we overlook the ones who cope because we never see them. It’s a

simple logical fallacy. You already have the answer, so you construct the

supporting argument. Trauma causes suffering, suffering causes damage. But what

we don’t know is whether the absence of adverse life events creates the ideal

conditions for human development. We just assume it does. And if damage does

somehow occur in a life lived behind the white picket fence, we must find something,

anything, the behavior of a parent, the death of a pet, and we call it the

inciting incident. You’re saying that if there was an incident, ergo there must

be damage. Equally if there is damage ergo there must be an incident. Both

logical fallacies. And what is life without incident? Is such a life even

possible?” He took a sip of his water. “How do we become human except in the

face of adversity?”

The good news is that those of us who are early childhood educators can have a lasting impact on building resilience in children who have experienced trauma. We can listen to children, build positive relationships and support them in a safe environment to help them either demonstrate the resilience that they already have, or support young children who need to build up those protective factors by being their rock. The better news is that, if we are doing the work, we do this for ALL kids. The phenomenon of resilience is so common that the researcher who has studied it the most deeply, Ann S. Masten has coined it as "ordinary magic." Resiliency is actually a more prevalent outcome from trauma than damage.

Early childhood educators have the skills to harness this "ordinary magic," but to do so, they need to start from a strengths-based lens as they teach and assess their students. While all of those statistics are real, they are current statistics and they do not have to define the future. And early childhood educators are in a strategic position to help change that trajectory.